Danielle Jacques and Alessandra Del Brocco

Abstract

The concept of a “just transition” away from fossil fuels and toward green energy alternatives captures the social implications of large-scale adaptations to the climate crisis and the importance of centering equity in these processes. To date, there is little research on regions receiving green energy that consider the gendered power dynamics undergirding the expansion of these technologies, particularly rural agricultural areas. In this paper, we interrogate the possibility of a “just transition” by presenting a case study highlighting the gendered nature of farmland loss as solar expands across central Maine’s “dairy belt.” We begin with a timeline of the land to demonstrate how patterns of settler-colonial expropriation and extraction persist in one of Maine’s poorest counties through economic and political maneuverings paving the way for solar energy production. We then explore the experiences of women tied to a fifth-generation family farm who returned to the farm later in life but had been, and continue to be, excluded from decisions around the future of the land. This exclusion is the latest form of reification of heteropatriarchal, colonialist systems of land management that puts capitalism first and community last. We assert that any approach to “just” energy transitions must break from ongoing cycles of dispossession and point to “feminist energy systems” as a potential path forward.

Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change, driven by unbridled carbon emissions, produces large-scale shifts in energy production away from fossil fuels and toward “green” alternatives like wind and solar. This energy transition has the potential to fundamentally reshape social life. The term “just transition,” which emerged from US labor movements of the late 20th century, describes a process of “greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind.”[i] Research on just transition tends to analyze it from two perspectives: factory work, and the production of fossil fuels. In both scenarios, workers “encounter difficulties in finding a new job because of a skills gap or are forced to make sacrifices such as substantial wage loss and long-distance commutes, along with compromises in culture, community identity, and sense of place.”[ii] However, this focus on labor risks emphasizing class relations in ways that obscure underlying dynamics tied to gender and race.[iii] This bifurcated analysis also tends to be spatially limited, privileging urban, industrial areas or rural communities at the center of the petroleum and coal industries. These studies do not capture the experiences of individuals and communities situated in regions receiving green technologies like wind turbines or solar panels.

To contribute an additional perspective to this literature, we interrogate the very notion of a “just transition” through examination of the under-studied implications of gender in the ongoing shift toward green energy,[iv] focusing on the expansion of solar and the subsequent loss of farmland in central Maine’s “dairy belt.” Our research consists of a historical timeline of land use in central Maine, contextualized through oral histories conducted in 2020 with three sisters shortly after their family’s land was sold and developed to support solar panels. We employ feminist methodologies designed to consider sustainability science (Staffa et al 2022), and focus on centering the experiences of women ignored in decision-making processes around the sale of their family’s farm. Without this documentation, their voices would be excluded from narratives of the land’s transition from agriculture to energy. By recentering their story, we offer important insights into alternatives to the hegemonic culture surrounding energy transitions in rural areas from a group that has been historically omitted from so many agrarian narratives: farm women.

Our argument unfolds in two parts. First, we situate our case study within a larger context of ongoing cycles of dispossession dating back to settler-colonial practices of expropriation and extraction leading to environmental devastation in the present-day.[v] We note that this pattern persists in the economic and political maneuverings making room for solar panels on land in one of Maine’s poorest counties.1 Second, we examine how these practices play out along gendered lines, highlighting how traditions of patriarchal succession, designed in part to separate women from land, enable solar expansion and the profitable production of green energy in rural Maine. We combine these macro- and micro-level analyses to critique any notion of “just transitions” as projects of linear development, moving us collectively from one point to another on a sliding scale towards equitable, green energy. Rather, energy transitions are multi-dimensional occurrences across space and time,[vi] are inextricably tied to certain places and pieces of land, and are dependent on cycles of dis- and re-investment that are inherently inequitable.

We shine a light on the “hidden abodes” of capitalist production,[vii] namely gendered labor/social reproduction and brutal alienation of people from the environment, to assert that any hope of “justice” in the context of energy transitions must break from these cycles. To that end, we point to the framework of “feminist energy systems”[viii] (FES), developed by Shannon Elizabeth Bell, Cara Daggett, and Christine Labuski, which engages feminism to deal with issues of power, “whether it is political power or fuel power.” FES “can reach far beyond simply providing a lens for understanding gender inequalities as they relate to energy production, use, or policy-making.” We include this framework as a potential path toward equitable transitions away from fossil fuels and toward energy democracy and community control of the land.

History of Land Use in Central Maine

Maine, a state located in the northeastern corner of the United States, is stolen land. For at least 13,000 years, bands of the Eastern Abenaki2 made their home in the Kennebec River valley, which runs from Mozôdupi Nebes (Moosehead Lake) to the coast. According to Mali Obomsawin and Ashley Smith,

“Wabanaki peoples have lived in extended kinship networks throughout and beyond our homelands, establishing expansive agricultural fields and villages, and moving seasonally between these and smaller family settlements in a sustainable fashion. When natural foods were in abundance in the summer months, we would live, farm, and harvest together in larger groups. In the colder months when food was scarcer, we would travel in smaller family bands and spread across the territories to find sustenance, mostly through hunting and trapping. These practices upheld kinship bonds with the animals and plants by ensuring that we would not overexploit one area or take more than we needed to survive.”

The Kennebec River was an important source of food, travel, and trade among Wabanaki peoples. The confluence of rivers and fertile land made the village of Narantsouak (anglicized to “Norridgewock”) a center of political and ceremonial life. “Narantsouak was literally the center of our world, where intertribal bonds and kinship relations were protected and maintained. It was a place of diplomacy, ceremony, agriculture, and trade, where families would gather and reunite regularly.”[ix] Wabanaki social structures were a combination of a people constantly in movement around the land and a network of permanent villages, neither of which aligned with European conceptions of relations between people, land, and property.

Early settlers, in their efforts to dispossess the Wabanaki of their land, composed treaties that were intentionally deceptive with respect to ownership rights.3 These treaties, and settlers’ refusal to respect them, gave way to conflict, which escalated until 1724 when New England colonists and allies attacked Narantsouak in the middle of the night, massacring not only local warriors and Chief Bomazeen but also women and children. Those who survived the violence fled northward to what is now Québec or eastward to take refuge in Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet communities. While some later returned to the area, there is no organized Kennebec band of Abenaki in Maine today.4 However, “the massacre at Narantsouak was by no means the end of the Kennebec tribe’s presence along their river.” Returned Kennebec peoples continued to resist settlers’ encroachment and defend their homelands, and to hunt and grow traditional foods in the area, well into the 19th century. “Today, there are entire families at Odanak, Wôlinak, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Nations whose lineage traces back to the Kennebec River. Descendants of the Narantsouak community, and the survivors of centuries of English and American warfare, have always remembered where we come from, and our ancestors interred there remember us. This land and water continues to draw us to it – whether we have been sheltered by kin in other communities for hundreds of years, or remained here all along.”[x] For these reasons, it is essential to recognize that the violence of settler-colonial dispossession and erasure is an ongoing, present-day process rather than a historical event.[xi]

Long-term efforts to eradicate the Wabanaki peoples from their homeland involved settlers taking advantage of the river valley’s fertile soils to bring much of the land into large-scale agricultural production. The temperate climate was especially good for grains and grasses, so forests were leveled and converted to rows of wheat and corn, as well as pastures for grazing dairy cows. Central Maine came to be known as the state’s “dairy belt.” The region’s agricultural economy peaked in the late 19th century, when over 70% of the area was in agricultural use, compared to just 13% in 1997.[xii] This decline was brought on by a tripartite economic shift from the late 19th century to mid- 20th century. First, as soil fertility on the East Coast plummeted, settler colonization expanded westward into the Great Plains, prompting the rapid expansion of American agriculture and making smaller New England farms obsolete. Second, as the Industrial Revolution gained momentum, an increasing number of mills were constructed along the Kennebec. The promise of stable wage work drew farmers away from the fields and into the factories in droves. Third and finally, the post-World War II mechanization of agriculture, particularly the introduction of tractors, expedited farmland consolidation and contributed to overall farmland loss.[xiii]

Subsequently, neoliberal policies of the late 20th century promoting economic liberalization and the shrinking of social safety nets brought further instability to central Maine. Many remaining farms were shuttered, squeezed out of the market by “get big or get out” farm policy. Similarly, the paper mills along the major rivers began to close one by one as industry relocated abroad. Today, there is ongoing debate regarding the potential for sustainable energy to fill an economic chasm left behind by agricultural decline and industrial abandonment. The state’s Office of Economic Development lists food/agriculture, along with forest products, marine/aquaculture, outdoor recreation, and clean energy among the “key industries” of Maine’s contemporary economy, centering these in its 10-year development strategy.[xiv] Of course, many of these intended areas of growth are in direct conflict with one another over competition for one key resource– land.

Agriculture, Industry, and Energy: Maine’s Dairy Belt in Transition

Agriculture, industry, and energy in central Maine left their mark on the environment, and the impact of this has become especially acute in recent years. In the latter decades of the 20th century, precisely when both farmers and nearby paper mills were facing unprecedented economic pressures, Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) approved a program allowing municipalities to dispose of industrial waste by offering it to farmers as free fertilizer. The sludge was made by mixing residuals from the mills’ chemical processes with human waste (and referred to by the innocuous term “biosolids”). Dairy farms across Maine took advantage of the biosolids program to reduce costs, hoping to fertilize their fields, increase hay production, reduce the need to purchase off-farm food supplies for their animals, and avoid being squeezed out. They were assured the sludge was safe.[xv]

The program lasted until 2016, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) conducted a series of tests on an organic dairy farm in Arundel, in southern Maine, and found high levels of unregulated contaminants in the water. Since then, hundreds of wells and wastewater facilities in Maine have tested positive for high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), so-called “forever chemicals.” 4 These chemicals, which can have adverse effects on “cholesterol levels, thyroid function, birth weight, liver function, infant development, the immune system, and may increase the risk of some cancers,”[xvi] do not break down in nature and therefore bio-accumulate in organic materials, including our bodies. As a result of this contamination, which was eventually linked to the DEP biosolids program, dozens of dairy farms across the state have had to pull their products, “detox” their herds, or close altogether.[xvii]

Meanwhile, solar energy development grew rapidly across the state, to the point that a local newspaper deemed the trend a “land rush.”[xviii] This was spurred by two state laws put into place in 2019, each intended to help the state reach its goal of converting 100% of its electricity to renewable resources by 2050.[xix] Before long, local communities began rallying in opposition to solar development projects in their towns.[xx] While explanations of this resistance are varied and context-specific, one report highlights three main causes: 1) solar production is land-intensive and can contribute to inflated real estate prices; 2) solar panels are seen as a “blight,” negatively affecting rural towns’ rustic appeal; and 3) online campaigns, led largely by Citizens for Responsible Solar (a lobbying entity with ties to the fossil fuel industry[xxi]) have effectively spread misinformation about the consequences of solar panel installations.[xxii] In Maine, solar quickly became a contentious topic, leading to more restrictive legislation and more rigorous (and slower) permitting processes for new solar development projects. Interestingly, as these two environmental issues (solar expansion and the discovery of PFAS contamination) coincided almost perfectly, the governor signed a new law that would prioritize PFAS-contaminated farmland for future solar development.[xxiii] The region’s rolling pastures, now akin to terra nullius,[xxiv] a literal “wasteland” contaminated with toxic “forever chemicals,” have proven especially well-suited for the installation of solar arrays.

The case study in question highlights many layers of exploitation of land over time, beginning with settlers clearing it for agriculture, industry using it as a low-cost space to externalize waste, and energy companies acquiring and outfitting it with solar panels. Furthermore, the environmental issues discussed above intersect at Green Knolls Farm, a fifth-generation family dairy farm in central Maine. In 2020, the family’s eighty acres were sold, amid much contention, to a multinational corporation for solar development. Shortly thereafter, the state paid for tests to be conducted on the property’s wells, which tested above the allowable limit for PFAS. While multiple family members attest that biosolids were never used on the land, the area around the farm is studded with confirmed “dump sites.” The farm, which never applied the contaminated fertilizer, had been impacted due to pervasive use throughout the community. High levels of PFAS chemicals leached into the water cycle over the course of several decades, making much of the land previously used for pasturing dairy cows unfarmable and, in some cases, indefinitely unlivable. This project discusses these intersecting environmental challenges from the perspective of farm daughters, who are tied to the property and have been affected in turn by each of these events (the farm’s sale and the subsequent discovery of PFAS), albeit without having any official control over the land itself. Through this discussion, we hope to illuminate what it means to endure loss amidst the “win-win” solution of fitting contaminated farmland with solar panels for green energy production.

Oral Histories: Uncovering Women’s Accounts of Land and Loss

While we examine themes of gender in relation to generational land loss and economic transitions, concepts that have been individually studied but rarely placed in conversation with one another, we prioritize the nuanced insights gleaned from both place-specificity4 and social intimacy.[xxv] As a result, the four interviews included here maintain an honest tone, a familiarity that lends itself to generational knowledge being passed on, as well as the shared experience of women in the family. This research benefits from decades of feminist scholarship and methodologies[xxvi] and acknowledges that rural studies are often best served by in-depth, qualitative methods like oral history or ethnography.[xxvii] As is the nature of oral histories and ethnographic research, the authors’ positionality, particularly the dual identity as community members and scholars, has intrinsically shaped this data.[xxviii] Specifically, we employ a feminist methodology informed by Rachel K. Staffa, Maraja Riechers, and Berta Martín-López, designed to center care in transdisciplinary sustainability science; care, in this instance, referring to “an attentive and power-critical commitment for the wellbeing of our world as composed of continually unfolding relationships and interdependencies between humans and all that is living and non-living.” [xxix] This nuanced approach to considering the needs of the community, the family, the land, and holding all three in the context of the past and potential futures allows us to critically and carefully examine the power at play in this energy transition.

We draw the data from four in-depth, unstructured interviews with three women, each tied in different ways to their family’s farm that had been sold a few weeks prior. The women recounted the stories of their lives, beginning with memories of growing up on the farm and ending with the painful experience of learning about the farm’s sale after the fact. The author who conducted these interviews (Jacques) is the daughter of one of the interviewees (Gretchen) and the niece of the other two (Cynthia and Catherine). As such, the interviewer is not a detached, third-party observer. Rather, she is privy to the details of how this process has affected her family through lived experience. The interviews unfolded over many hours of conversation with her mother and aunts and, if not for the COVID-19 pandemic, they would have taken place at a kitchen table over coffee (instead, they were recording over a series of video calls).

The author’s proximity to the situation did not come without challenges to the research process. Although a solo project interviewing family members has the potential to produce biased insights, we navigated this possibility by having Del Brocco, who has no immediate relation to anyone in the study, transcribe the interviews verbatim before analyzing and inductively coding them using NVIVO. This made space for constant dialogue between the authors around reflexivity as both engaged in different ways with the data. Apart from this strategic division of data collection and processing, the writing process was collaborative.

The following section explores the experiences of the three women with particular attention paid to Gretchen and Cynthia, both of whom returned to the farm as adults, just before the land was sold by a male nephew without their knowledge or consent. Their biographies offer an under-utilized vantage point in discussions of justice in relation to energy transitions, namely a critical feminist perspective on patrilineal land tenure practices manifesting through relationships to land, on-farm labor, and loss. We embed these conversations within the broader literature on the gendered nature of farmland succession to help illuminate the stories of the otherwise invisible farm daughters experiencing green energy development in an economically depressed town in rural Maine.

Gender and Labor on Green Knolls Farm

Gretchen and Cynthia, the two youngest of six siblings, are members of the fifth generation born and raised on Green Knolls Farm. They grew up working alongside their parents (Robert and Muriel), two older brothers (Brian and James), and two older sisters (Catherine and Leanne), milking cows, stacking hay, and tending the garden that fed the family. It was understood, though unspoken, that their eldest brother, Brian, would take over the farm someday and inherit the property in its entirety.

Despite her interest in learning the technical skills needed to farm successfully, Gretchen was not allowed to participate in on-farm tasks that would have developed her abilities to do so in the future. One of the more contentious points was her desire to work the tractor.

Gretchen: “Girls did not really drive tractors… [my father] let me do the raking like, once or twice when I was in high school, which did require driving the tractor, but he set everything up and I just drove it in a circle around the field. But for the most part, the only thing the girls did– we would drive the tractor while they were loading the hay, because they would put it on low gear, all we had to do was steer…in a row…”

This is illustrative of the highly gendered division of labor on the farm. Gretchen says her father tried to “protect” the girls from the “really hard, gross work;” instead, she remembers being tasked with pulling weeds in the garden, labor her brothers were never asked to do, because this was considered “girl work.” Above, she notes that girls were permitted to drive the tractor while the boys loaded hay, which was the more physically demanding of the two jobs. Cynthia, the youngest, similarly described her father’s refusal to allow his daughters to operate the farm equipment as benevolent.

Cynthia: “My father was really very open-minded and progressive that way. He always understood the woman as a weaker sex, because I remember growing up, [Gretchen] wanting to learn how to, I think, rake hay…. They started to teach her, but I think my father was very uncomfortable with women on the equipment because we didn’t have the physical strength that we might’ve needed. But I don’t think he was ever one to say a woman can’t do the job, per se, I think that he truly understood that women play an integral part in the business world.”

While acknowledging her father’s cursory understanding of the contributions his daughters’ labor made to the family business, Cynthia also reveals that his understanding of what it took to successfully run the farm was inextricably tied to biological maleness, rationalized through perceptions of differing physical abilities between men and women. However, this rationalization does not align with the observations of Catherine, the eldest sister, who pointed out that the male children in the family were taught to drive the tractor at a very young age.

Catherine: “And not that he didn’t work hard, don’t get me wrong he worked very hard, but that separation, of this is women’s work and this is men’s work. You know, it was like– I never got to drive the tractor when I was little, I mean I was 4 years older than James and he could drive the tractor when he was six or seven and could barely reach the pedals, but I couldn’t drive the tractor because I was a girl.”

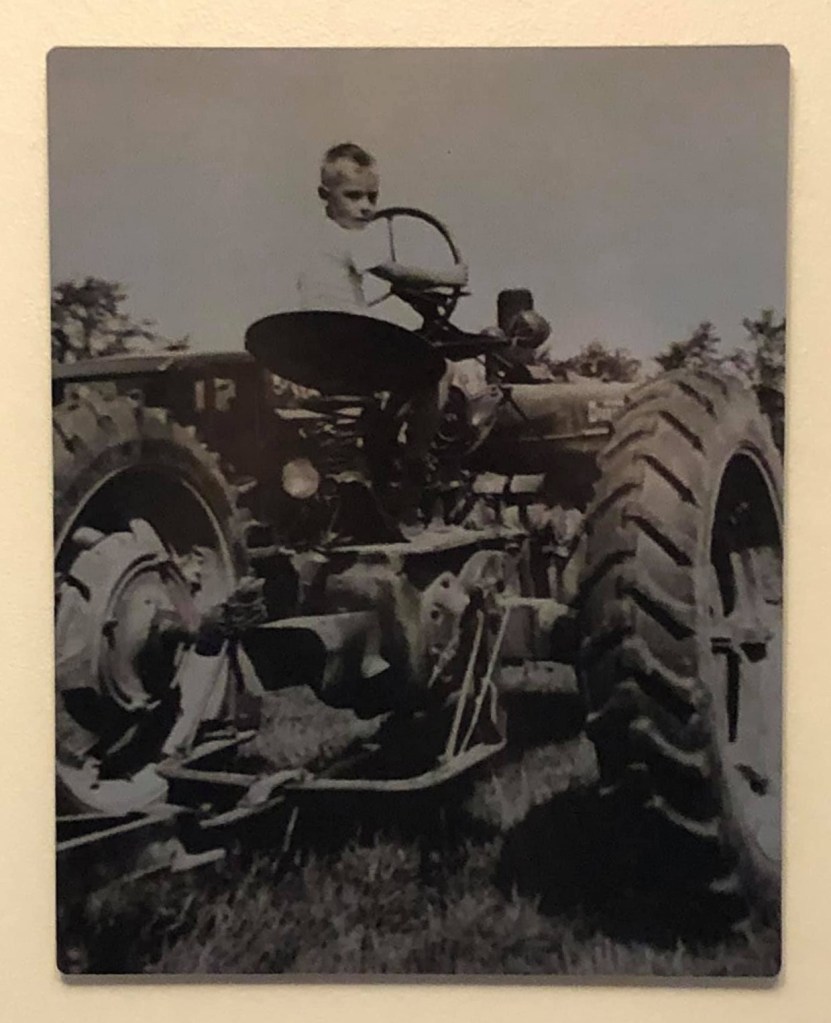

Here, we see Brian at a very young age, posing on the family’s tractor. The eldest son was not only permitted but also encouraged from a young age to embody the role of the farmer. His sisters, on the other hand, received inverse treatment throughout their lives, tasked with chores pertaining to the reproduction of the domestic sphere rather than production for market.

These reflections align with recent research demonstrating how widespread cultural narratives tied to on-farm socialization shape not only labor but also access and entitlement to land along gendered lines. Farming as a profession, especially the use of heavy farm equipment like tractors, is still broadly understood as masculine.[xxx] The rationale of who can and cannot use the farm equipment is one of many “cultural scripts” derived from a “long-standing cultural requirement and the product of collective thinking” that purports to benefit the whole family unit, upholding hegemonic masculinity via farm-specific tropes and practices.[xxxi] In particular, the construction of a successor identity over the course of the eldest male child’s life naturalizes their accession to the head of the family, the sole decision-maker, later in life.[xxxii] In this way, children are taught to embody the gendered constructions of successor and non-successor identities, and entitlement to land becomes naturalized by tying land to bodies that can “do” farming and, therefore, “be” farmers. The example of Gretchen being denied the right to learn the same skills as her brother highlights the processes of socialization that reproduce differential access to knowledge and resources as well as the cultural scripts that justify these differences. In this way, farm daughters may internalize dominant narratives and ultimately accept the gentle, almost imperceptible “symbolic violence” of inequitable transfers of power through succession.[xxxiii]

Women’s Experiences of Belonging and Loss

Such socialization would prove to have material consequences for the whole family as the siblings, their parents, and the farm itself aged. As adults, Gretchen and Cynthia moved away and Brian dutifully returned to the farm after college to help his parents eke out a living. The business experienced some growth during the 1970’s, but the local dairy industry began to contract again in the 1980’s and remained steadily in decline from then on.[xxxiv] Brian took an off-farm job to make ends meet. In the 1990’s, Gretchen returned to the area, hoping to build a house on her family’s land. Instead, the pastures remained in farming until their father’s death in 2007.

At this time, Gretchen and her older sister, Leanne, began to assume more responsibility for the care of their mother, Muriel, who lived alone in the house across the street from the milking barn. Brian began to downsize the farm. The farm eventually closed altogether in 2009, when he made the difficult decision to sell the herd. Still, Brian did not agree to sell Gretchen any of the land. Instead, she purchased nine acres and built her home on a plot of land adjacent to one of the pastures, sharing a stone fence with the farm along one side.

Gretchen: “Yeah, this was all covered with trees and like tall, tall, tall weeds. This was a really nice farm when I was growing up. The people’s house was on the other side of the road, it was a beautiful white farmhouse, and so that land unfortunately sold first, and then this one was just sitting here. So, trying to– I don’t know, I was just really motivated. Sometimes I get really stuck in my head that I’m going to do something, regardless of consequences, and I really wanted to be out in the country… I wanted to have a garden, I wanted to be part of that, in my head daydreaming about like oh it’s gonna be like this or like that.”

When Muriel died in 2011, Brian agreed to sell the now-empty house to Cynthia. The sale included the house, the land underneath it, a portion of the stream that ran through some woods on one side, and a small, abandoned apple orchard– about ten acres in all. While this transaction was not in the will, Cynthia insists it was in line with her parents’ wishes to keep the farmable pastures together. Indeed, her desire to “preserve” what her parents had worked for motivated her decision to return to the farm in the first place.

Cynthia: “I can’t tell you what it was, there isn’t any one thing that said “come back.” It was just, a lot of the memories, a lot of wanting to… I wanted to preserve the heritage that was my grandparents and my parents and even Brian’s to an extent… It was just something in my soul that said that I had to go home. I knew that I was giving up a lot to come home. I was not far from being eligible to retire, not that I would’ve. But, my life was quite easy at that point. Came back, and it hasn’t been so easy. And we still, the house needed a tremendous amount of work and it still needs a tremendous amount of work. We’ve worked outside a lot. Well, we walked away from a lot. We gave a lot up, but when we came back and you stand outside and you have a childhood memory of, oh I played here. I have a picture somewhere of me, I’m sitting on a rock in the brook and I’m soaking my feet. We’d been out working and my feet were hot and tired. And just sitting there on my rock just soaking my feet. Letting the world go by. It was slower, it was, so much of it was to preserve, I just wanted to preserve everything that my parents had worked for and loved.”

Gretchen expressed a similar sentiment about her return to the farm later in life. When asked why she decided to purchase this piece of land, which she admitted was overpriced and mostly useless wetland, when she could have bought better land for cheaper elsewhere, she replied:

Gretchen: “For one thing, it’s home, which, I don’t know if you ever get that feeling or not, when you come here, that, like a sense of home, and like, sitting on the porch, and– I mean, it is stupid in many ways, but the skyline… that’s what I grew up with, and it makes me feel at home, like it’s my place. Um… and so, and looking over at the barn, and seeing it, it’s home. Um… yeah. I mean, it probably would have been smarter to buy someplace else and not be so attached to it, it would be so much easier to not be attached to it, because now it’s lost, something I never, ever thought was going to happen.”

These musings highlight how, for the sisters, the land was far more than a commodity to be bought and sold with each passing economic cycle. In fact, rendering the land as a commodity through its sale was antithetical to their understanding of it as a social entity, one that remained steadfast in place and resisted change over time. The farm played an active role in the trajectory of their lives– so much so that they each felt compelled to return to it in a way that defied any logic of economic rationality. The preceding passages highlight how these women’s interactions with the land are intentionally relational and framed by an ethos of care, rather than transactional and framed by the logic of the market. The women are socially, as well as physically, embedded in the landscape, an observation that has been noted elsewhere.[xxxv] Yet, as non-successors, they lacked official, legal control over the land.

The farm itself remained in Brian’s hands for several more years. He continued haying the pastures to sell to other farms nearby. He also planted a pumpkin patch and sunflowers to sell at a small farm stand in October. When he died unexpectedly in 2020, the family was sent into a whirlwind. At the time of his death, it was understood that the land would pass to his eldest son, Chris, who had been estranged from his father for several decades. Brian and Cynthia discussed other possibilities before his death regarding the future of the farm, as any decision with respect to the land would affect her now that she lived directly in the center of it. Gretchen, now approaching retirement, was in a similar predicament. When asked about these conversations, Cynthia replied:

Cynthia: “Well, I think, though, and in all honesty going back generational, [the farm was passed down] father to son, father to son, father to son. And I know Chris was very angry that he would’ve had to pay a nominal fee and wasn’t being given [the land] outright. Which, had he played his cards right, he probably would’ve gotten it for much less than the nominal fee was. Don’t know, we all asked him to come talk to us. We were gonna offer to either buy it, or at least to help him buy part of it but he wouldn’t. He just shut us off completely. [W]e had talked about how much [my son] Curtis had wanted to come here and wanted to farm. Knew it was gonna be a few years and everything. I still think that Brian had that father-to-son, ‘I wanted this for my children…’ I do think that that was…I’m quite sure he thought Chris would do the right thing, knowing what the property, what the farm, what the heritage meant to everyone. That this was a very special place.”

In the end, Brian’s will stated that his son had first right of refusal, and Cynthia was second in line to be able to purchase the land. The intention was simple: to keep the farm in one piece and in the family. This decision is consistent with research demonstrating that women are not taken seriously as potential successors unless there are no male heirs available or willing to take ownership.[xxxvi] Furthermore, women who do accede to a managerial role on the family farm and/or those who do own their land are not seen as ‘powerholders,’ but ‘placeholders’ until a male partner or heir comes along to take over.[xxxvii] In this case, Cynthia would have been both: a successor only if the “true” heir, the eldest son, recused himself, and then a placeholder until her son was able to make productive use of the land as the farmer.

Instead, the entire farm passed to Chris, despite Brian’s eldest child being a daughter and despite the fact that Chris was removed from the land, having lived many miles away for his entire adult life. He then sold the farm directly to a solar development company that had been interested in leasing the land prior to Brian’s death. This took place without any communication between Chris and the rest of the family regarding his plans, without hearing others’ views on what ought to be done with it. Chris’s decision to immediately sell the farm, disregarding his female family members’ physical presence on or adjacent to the land, highlights that for him, the value of the land was transactional rather than relational, social, or sentimental. The sale foreclosed on any possibility of reaching a more equitable outcome for everyone affected.

Cynthia: “And that was [Brian’s] wish too, that the farm, he really wanted the farm to stay in the family. He really did not want it to be subdivided. He had told me, he said, this was before he got sick he said, ‘Well, I got approached about leasing the land for a solar farm’ which is just disgusting but that’s beside the point. He says ‘You know, I could do that, and I could really make enough money that I could preserve the buildings.’ And then he got sick and nothing ever transpired with that. And um, the rest is pretty much history. As far as what happened and why what happened I can only speculate. And I’m not, that wouldn’t be fair to Brian. I just know, you know it was, it was ripped out, away from the family. And it will be a solar farm. We know that for a fact.”

Both Cynthia and Gretchen returned to the land as adults heading into retirement, to the place that felt like home, to live out the rest of their lives. As children, both were barred from gaining access to the skills necessary to be seriously considered as successors later in life. As adults, both acted on lifelong place attachment to the farm by moving back to the area. However, due to deeply embedded gendered inequalities reproduced across generations through heteropatriarchal succession practices, both were barred from gaining access to the land that would have allowed them to meaningfully reconnect with their past and preserve the history of their family’s land into the future. As a result, both settled for marginal lands adjacent to the once-fertile, now-contaminated farmland their parents had lovingly cared for, watching powerlessly as the farm’s pastures were sold without their input.

Gretchen: “I just wanted to be able to have a garden, and you know, can some vegetables before I died, because everybody, you know, I just felt like I missed out on all of that. That I had an opportunity to do it, and I had hoped to maybe, have some farm animals. Um… and, you know, have a little tractor. It’s very depressing… I mean, it’s nice to have the chickens. I wanted to eventually get a horse and I don’t know… I’m too tired. I’m- you know I have these, like everybody you have daydreams about how you think it might be, and the reality of that tends to be very different than your daydreams. But… I do have chickens. I do have a garden.”

Gretchen’s dream of moving to the countryside was enmeshed with visions of an agrarian lifestyle that she had “missed out on,” an attachment to her family’s land which she had no control over. She carried a desire to have farm animals and “a little tractor” of her own over the course of her entire life. Similarly, Cynthia shares that when she heard the news of the final sale, she couldn’t look out the window for several days. The thought of the farm’s pastures being covered in solar panels was too painful.

Cynthia: “Yeah, in my opinion, Danielle, it was done out of pure hate. I think it was done out of pure hate. And um, I expect the barns, everything on the other side of the road I expect to be, to see it all torn down. And the bridge will be rebuilt to make it, obviously, more convenient for them. So, I don’t know. That’s down the road. But the reason that I came home and the reason that I will stay here, even with the solar panels all around, is for the same reason that I came back here. It’s in my soul. This is where I belong.”

Gender, (Stolen) Land, and the Possibility of Energy Justice

The oral histories presented here illuminate the experiences of two women in one rural, economically-disadvantaged, historically agricultural community as they negotiate their experiences of acute loss. The sale of their family’s farmland is a form of social displacement central to the churn of corporate consolidation as industries cycle through rural space, treating land as a commodity rather than part of the social ecology of place.6 The logic behind social constructions of gender relates to control over land, specifically illustrated by these women’s relationships to land which are steeped in social meaning rather than being exclusively transactional or “logical.” Their invisible labor, both as children carrying out their daily chores and as adults caring for their aging parents, as well as their reflections on their emotional connection to the land, reveals the hidden impact of gendered inequalities underpinning ongoing energy transitions in rural areas.

Specifically, patrilineal succession practices on farms continue to serve capitalist imperatives in ways that separate women from land. While women benefit for a time from their family unit’s ownership of the land, they also suffer from its loss due to their subordinate position within that family unit. The cultural scripts noted above, which prioritize the “collective good” of the family by keeping the land from being subdivided over the individual needs and desires of farm daughters, ensure that the women are taught to accept this fate. Social norms around farmland succession continue to perpetuate heteropatriarchal patterns of power consolidation and resource accumulation. These processes can be traced back to early modes of settler-colonial expropriation and expansion and remain visible in each economic cycle the land has seen since then. The constant cycling of different iterations of patriarchal, capitalist land management structures includes the current transition of the land from agrarian use to more profitable energy use, an adjustment that will stand until the next more profitable land-based enterprise emerges.

The experiential particularities revealed here are tied to our interviewees’ identities as heterosexual, white women, having cursorily accessed and ultimately lost land as a direct result of their position within a family of Anglophone settlers. Though a comprehensive analysis of the intersecting implications of race, ethnicity, nationality, ability, and family/sexuality in relation to land access is outside the scope of this paper, we recognize that gender is only one factor that shapes the injustice of displacement in our case and similar cases across the United States. In an attempt to understand the deeply emotional, inextricably gendered loss of home experienced by these two women, we have also considered the various ways the land has been lost over time, beginning with the original and ongoing trauma of dispossession experienced by the Wabanaki, which made it possible for our interviewees to feel as though they “belong” to this land, and continuing to the present (and future) issues of chemical contamination. While these historical episodes are connected through patriarchal and settler-colonial logics of land tenure that drive resource accumulation into the hands of the few, we are not suggesting that they are the same. Rather, we note that the redundancy of the traumatic removal of people and resources from this specific geographic site is cyclical and that this needs to be taken into consideration within the renewable energy sector.

Furthermore, while this case study is place-specific, its implications relating to gender, land access, and green energy may prove relevant in other areas of the country in the years to come. By some estimates, about 70% of all farmland will change hands between 2011 and 2031,[xxxviii] and research shows that daughters are considered less than 5% of the time for succession of family businesses.[xxxix] Beyond this, multiple studies demonstrate that women face disproportionate hurdles in acquiring land to farm[xl] and that women are systematically excluded from agrarian processes.[xli] This paper details how the gendered inequalities tied to ownership, access, and control of farmland in the United States are passed on as the land transitions into green energy via, in this case, solar development. The earth is yet again stripped of its resources, people are re-traumatized along with it, and the cycle continues unabated. Any approach to achieving energy justice in this context, therefore, must be invested in fundamentally breaking this cycle and forging new relationships among and between people and land.

Conclusion: Toward a “Feminist Energy Systems” Approach

In this paper, we outlined the historical, geographic, and economic overview of central Maine to contextualize the land where our case study is situated within a broader history of dispossession and displacement. We then turned to the experiences of the women we interviewed to parse out how gender played a central role in the fate of the farm in question, particularly through on-farm socialization and the naturalization of patrilineal succession practices from one generation to the next. We hope that by threading together instances of ongoing dispossession (by theft)[xlii] and loss (by sale), unrelenting capitalist industrialism, and gendered social inequities rooted in colonial logics of land tenure, we might open new space in conversations about green energy. While incomplete, this effort expands the boundaries around conversations of “just transitions” by centering settler-colonialism and patriarchy as foundational structures[xliii], both of which continue to shape differential access to and exploitation of land. We shed light on a process that still has time to adjust its trajectory by pushing the conversation toward frameworks acknowledging ongoing processes of dispossession,7 land loss, and gender inequality in the agrarian and green energy sectors.

The ongoing energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables has the potential to reshape not only the physical world, but the social world as well. What this new world will look like is still largely undetermined. In an effort to stave off climate pessimism,[xliv] we turn to Bell et al. (2020), who put feminism’s “expertise in the study of power” to work for the climate crisis to inform the energy sector via a framework they refer to as “feminist energy systems” (FES). They write: “By injecting a feminist politics into energy, we aim to redirect political power from the pursuit of private profit to the pursuit of communal wealth, which will involve building new legal and geopolitical landscapes that are unlikely to be consistent with status quo hegemonic interests. To begin with, a feminist energy politics means more than adding renewable fuels to the grid. Feminist energy aims to transform energy (and sociopolitical) regimes into communally designed, owned, and managed systems.”[xlv] By including feminist politics and other historically marginalized perspectives such as queer ecologies and Indigenous epistemologies, we can imagine and act towards an energy future that disrupts the cycles of patriarchal, colonialist, capitalism-driven transitions that we have identified in this paper.

Interestingly, some scholars have pointed out that solar energy, in particular, lends itself to decentralized, democratic, community-based power structures.[xlvi] As we’ve seen, this is far from inevitable. An FES approach to solar development, one that is “continually attuned to how gender combines with other interlocking modes of oppression, including race, class, ethnicity, nationality, ability, sexuality, Indigeneity, colonial history, and Global North/South divides” would recognize the expansion of solar development as a social and cultural as well as technological and economic challenge, and provide communities with the tools to address each component rather than prioritizing productivity and profits over all else. In short, a future of feminist energy systems begins with looking to the past. To build the carbon-neutral world we need, through processes that prioritize equity over the status quo, we must understand and address the hidden social power structures embedded in the land and carried over from one cycle of use to the next.

Notes

- The farm in this study is located in Somerset county. In 2021, according to Maine’s Center for Workforce Research and Information, Somerset had the second-highest poverty rate in the state at 17.8%, compared to the national average of 12.6%. https://www.maine.gov/labor/cwri/county-economic-profiles/countyProfiles.html

- In their 2020 essay “The Wabanaki of the Kennebec River,” Obomsawim and Smith point out that “Abenaki is a mistranslation and mispronunciation of Wôban-aki, our word for describing the land and ourselves, which signifies the People of the Dawnland, the First Light, or simply of the East” (1). However, “[w]hile ‘Abenaki’ was not originally its own tribal entity, and could have historically been equated with Wabanaki, it has developed its own significance in the colonial context, and now describes the tribal peoples originating from central Maine westward to the loose boundary of Lake Champlain and the Hudson river. The tribal communities of this region have been categorized into the ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western Abenaki’ by linguists and historians, together comprising over twenty tribes of origin, whose stories intersected and diverged throughout the colonial wars” (1).

- Boardman writes in A general view of the agriculture and industry of the county of Kennebec : with notes upon its history and natural history, the Abenaki “did not understand how one person could own a certain tract himself, as each native possessed the undivided right to the entire territory of his tribe. When the land was purchased by the whites, they supposed they possessed a title in fee simple– on the other hand, the Indians supposed they sold only what they themselves possessed– viz: the right to fish and hunt and hold possession with others. Thus the Indians were compelled to yield to what they regarded as injustice, which was cause for serious trouble between them” (Boardman 1865, 3).

- Historical research on this event is scarce and tends to glorify the martyrdom of a Catholic missionary in residence at Norridgewock. There are conflicting accounts of who was there and how many people were killed. These inaccurate, white-washed accounts of the event are part of ongoing erasure of Indigenous histories. While admittedly incomplete, the events laid out here are drawn from a local, independent newspaper. https://townline.org/the-kennebec-indian-tribe/

- Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection has created a map of contaminated sites across the state, which can be accessed at: https://maine.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=468a9f7ddcd54309bc1ae8ba173965c7

- As Billings and Kingsolver note in their introduction to Appalachia in Regional Context: Place Matters, “Place matters, more than ever, in relation to the construction of identity and meaning, politics and policy, citizen activism, creative expression, and in scholarship, research, and teaching.” (6) For this study, their conception of praxis of place informs the autonomy and struggle of rural communities: “It is about what people do- in one way or another, in concert, contestation, or consternation- as they try to make sense of and live with the nearby and distant forces in their lives” (Billings and Kingsolver 2018, 7).

- Continuing with Billings and Kingsolver’s beautiful description of the importance of place, we agree that “the bumpy, recalcitrant friction of the local [is] often argued by neoliberal capitalist enthusiasts [to have been] smoothed over-and for the good of all. But that is not the case…One-sided talk about information technologies that shrink time/space distances and augment top-down, corporate globalization has the effect of eclipsing-even denying- the continuing importance of place. Yet people still live and die in places, leave places, and move to new places” (Billings and Kingsolver 2018, 6).

- As Nichols states in Theft is Property! Dispossession & Critical Theory, although dispossession can take on a presence “as a gravitational center,” it is not “a singular concept” or moment in land/space history but an ongoing process that “brings together shifting configurations of property, law, race, and rights” (Nichols 2020: 6).

[i] Tavares, Marcia. “A Just Green Transition: Concepts and Practice so Far.” Policy Brief. Future of the World. United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-no-141-a-just-green-transition-concepts-and-practice-so-far/.

[ii] Wang, Xinxin, and Kevin Lo. “Just Transition: A Conceptual Review.” Energy Research & Social Science 82 (December 1, 2021): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291.

[iii] Luke, Nikki. “Just Transition for All? Labor Organizing in the Energy Sector Beyond the Loss of ‘Jobs Property.’” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113, no. 1 (January 2, 2023): 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2079471.

[iv] Johnson, Oliver W., Jenny Yi-Chen Han, Anne-Louise Knight, Sofie Mortensen, May Thazin Aung, Michael Boyland, and Bernadette P. Resurrección. “Intersectionality and Energy Transitions: A Review of Gender, Social Equity and Low-Carbon Energy.” Energy Research & Social Science 70 (December 1, 2020): 101774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101774.

[v] Whyte, Kyle. “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice.” Environment and Society 9, no. 1 (2018): 125–44. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2018.090109.

[vi] Harvey, David. Spaces of Capital : Towards a Critical Geography. New York: Routledge, 2001.

[vii] Fraser, Nancy. “Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode.” New Left Review, no. 86 (April 1, 2014): 55–72.

[viii] Bell, Shannon Elizabeth, Cara Daggett, and Christine Labuski. “Toward Feminist Energy Systems: Why Adding Women and Solar Panels Is Not Enough.” Energy Research & Social Science 68 (October, 2020): 101557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101557.

[ix] Obomsawin, Mali and Ashley Smith. “The Wabanaki of the Kennebec River.” (2020). https://gradfoodstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/39f1a-thewabanakiofthekennebecriver.pdf

[x] Ibid. “The Wabanaki of the Kennebec River.”

[xi] Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 1, 2006): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

[xii] Ahn, SoEun, William B Krohn, Andrew J Plantinga, and Timothy J Dalton. “TB182: Agricultural Land Changes in Maine: A Compilation and Brief Analysis of Census of Agriculture Data, 1850-1997.” Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 182. (2002).

[xiii] Ibid. “Agricultural Land Changes in Maine: A Compilation and Brief Analysis of Census of Agriculture Data, 1850-1997.”

[xiv] “Key Industries,” Maine Office of Business Development. http://www.maine.gov/decd/business-development/move/key-industries. Accessed 15 July 2023.

[xv] Perkins, Tom. “‘I Don’t Know How We’ll Survive’: The Farmers Facing Ruin in America’s ‘Forever Chemicals’ Crisis.” The Guardian, March 22, 2022, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/22/i-dont-know-how-well-survive-the-farmers-facing-ruin-in-americas-forever-chemicals-crisis.

[xvi] Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry. “Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) – Bureau of Agriculture, Food and Rural Resources: Maine DACF.” Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/ag/pfas/index.shtml#impact.

[xvii] Overton, Penelope. “A Forever Farm Is No Match for Forever Chemicals.” Press Herald, June 11, 2023. https://www.pressherald.com/2023/06/11/a-forever-farm-is-no-match-for-forever-chemicals/.

[xviii] Turkel, Tux. “Unprecedented Wave of Solar Development Spurs Land Rush in Maine.” Portland Press Herald (January 5, 2021). http://www.pressherald.com/2021/01/04/unprecedented-wave-of-solar-development-spurs-land-rush-in-maine/.

[xix] “Solar.” Solar | Governor’s Energy Office, http://www.maine.gov/energy/initiatives/renewable-energy/solar-distributed-generation#State%20Policy. Accessed 21 Aug. 2023.

[xx] Russel, Lia. “Although Solar Panels are Multiplying, Maine Towns Start to Halt Construction.” Maine Public. (November 1, 2021). https://www.mainepublic.org/environment-and-outdoors/2021-11-01/although-solar-panels-are-multiplying-maine-towns-start-to-halt-their-construction

[xxi] Green, Miranda, Michael Copley, and Ryan Kellman. “An activist group is spreading misinformation to stop solar projects in rural America.” National Public Radio. (February 18, 2023). https://www.npr.org/2023/02/18/1154867064/solar-power-misinformation-activists-rural-america

[xxii] Groom, Nicola. “U.S. solar expansion stalled by rural land-use protests.” Reuters. (April 7, 2022) https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-solar-expansion-stalled-by-rural-land-use-protests-2022-04-07/

[xxiii] Ogrysko, Nicole. “New Law May Give PFAS-Contaminated Farms an Alternative Income Source through Solar.” Maine Public. (June, 23 2023). http://www.mainepublic.org/environment-and-outdoors/2023-06-27/new-law-may-give-pfas-contaminated-farms-an-alternative-income-source-through-solar.

[xxiv] Griffin, Carl J. “Enclosure as Internal Colonisation: The Subaltern Commoner, Terra Nullius and the Settling of England’s ‘Wastes.’” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 1 (December 2023): 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440123000014.

[xxv] Billings, Dwight B. and Ann E. Kingsolver. Appalachia in Regional Context Place Matters. Place Matters: New Directions in Appalachian Studies. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2018.

[xxvi] Reinharz, Shulamit. Feminist Methods in Social Research. New York: Oxford University Press. 1992.

[xxvii] Scott, S. L. “Drudges, Helpers and Team Players: Oral Historical Accounts of Farm Work in Appalachian Kentucky.” Rural Sociology 61, no. 2 (1996): 209–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1996.tb00617.x.

[xxviii] Barton, Bernadette. “My Auto/Ethnographic Dilemma: Who Owns the Story?” Qualitative Sociology 34, no. 3 (September 2011): 431–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-011-9197-x.

[xxix] Staffa, Rachel K., Maraja Riechers, and Berta Martín-López. “A Feminist Ethos for Caring Knowledge Production in Transdisciplinary Sustainability Science.” Sustainability Science 17, no. 1 (January 2022): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01064-0.

[xxx] Saugeres, Lise. “Of Tractors and Men: Masculinity, Technology and Power in a French Farming Community.” Sociologia Ruralis 42, no. 2 (2002): 143–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00207.

[xxxi] Chiswell, Hannah M., and Matt Lobley. “‘It’s Definitely a Good Time to Be a Farmer’: Understanding the Changing Dynamics of Successor Creation in Late Modern Society.” Rural Sociology 83, no. 3 (2018): 630–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12205.

[xxxii] Fischer, Heike, and Rob J. F. Burton. “Understanding Farm Succession as Socially Constructed Endogenous Cycles.” Sociologia Ruralis 54, no. 4 (October 2014): 417–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12055.

[xxxiii] Conway, Shane Francis, John McDonagh, Maura Farrell, and Anne Kinsella. “Uncovering Obstacles: The Exercise of Symbolic Power in the Complex Arena of Intergenerational Family Farm Transfer.” Journal of Rural Studies 54 (August 1, 2017): 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.007.

[xxxiv] Griswold, Ellen S. “Dairy Sector Report.” State of Maine Agricultural Report Series. January, 2020. https://www.mainefarmlandtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Dairy-Sector-Report.pdf

[xxxv] Trauger, Amy, Carolyn Sachs, Mary Barbercheck, Kathy Brasier, and Nancy Ellen Kiernan. “‘Our Market Is Our Community’: Women Farmers and Civic Agriculture in Pennsylvania, USA.” Agriculture and Human Values 27, no. 1 (March 2010): 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9190-5.

[xxxvi] Glover, Jane L. “Gender, Power and Succession in Family Farm Business.” Edited by Dr Lorna Collins, Dr. Haya Al-Dajani, Dr. Zografia Bika, and Dr. Janine Swail. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 6, no. 3 (September 2, 2014): 276–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-01-2012-0006.

[xxxvii] Carter, Angie. “Placeholders and Changemakers: Women Farmland Owners Navigating Gendered Expectations.” Rural Sociology 82, no. 3 (2017): 499–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12131.

[xxxviii] Carolan, Michael. “Lands Changing Hands: Experiences of Succession and Farm (Knowledge) Acquisition among First-Generation, Multigenerational, and Aspiring Farmers.” Land Use Policy 79 (December 2018): 179–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.08.011.

[xxxix] Wang, Calvin. “Daughter Exclusion in Family Business Succession: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 31, no. 4 (December 2010): 475–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9230-3.

[xl] Fremstad, Anders, and Mark Paul. “Opening the Farm Gate to Women? The Gender Gap in U.S. Agriculture.” Journal of Economic Issues 54, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 124–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2020.1720569.

[xli] Beach, Sarah S. “‘Tractorettes’ or Partners? Farmers’ Views on Women in Kansas Farming Households.” Rural Sociology 78, no. 2 (2013): 210–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12008.

[xlii] Nichols, Robert. Theft Is Property! Dispossession & Critical Theory. Radical Américas. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

[xliii] Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. “Settler Colonialism as Structure: A Framework for Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1, no. 1 (January 2015): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214560440.

[xliv] Higgins, David. “Climate Pessimism and Human Nature.” Humanities 11, no. 5 (2022): 129. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050129.

[xlv] Ibid. “Toward Feminist Energy Systems: Why Adding Women and Solar Panels Is Not Enough.”

[xlvi] Buechler, Stephanie, Verónica Vázquez-García, Karina Guadalupe Martínez-Molina, and Dulce María Sosa-Capistrán. “Patriarchy and (Electric) Power? A Feminist Political Ecology of Solar Energy Use in Mexico and the United States.” Energy Research & Social Science 70 (December 1, 2020): 101743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101743.

Biographies

Danielle Jacques (M.A. Gastronomy, Boston University) is a second-year doctoral student in Sociology at Brandeis university specializing in community and environmental sociology. She is currently working on a research project with community land trusts (CLTs) in the Boston area. You can learn more about her work at daniellemjacques.com.

Alessandra Del Brocco (M.A.) is an all-but-dissertation doctoral candidate at the University of Kentucky, where she studies the intersections of food systems, gender, and sexuality. Her forthcoming dissertation examines the role of LGBTQ+ farmers in the development of sustainable agriculture and in their local food systems. Alessandra currently lives in Berea, Kentucky. You can learn more about her work at alessandradelbrocco.com.