Mahika Mor & Shreya R

Introduction

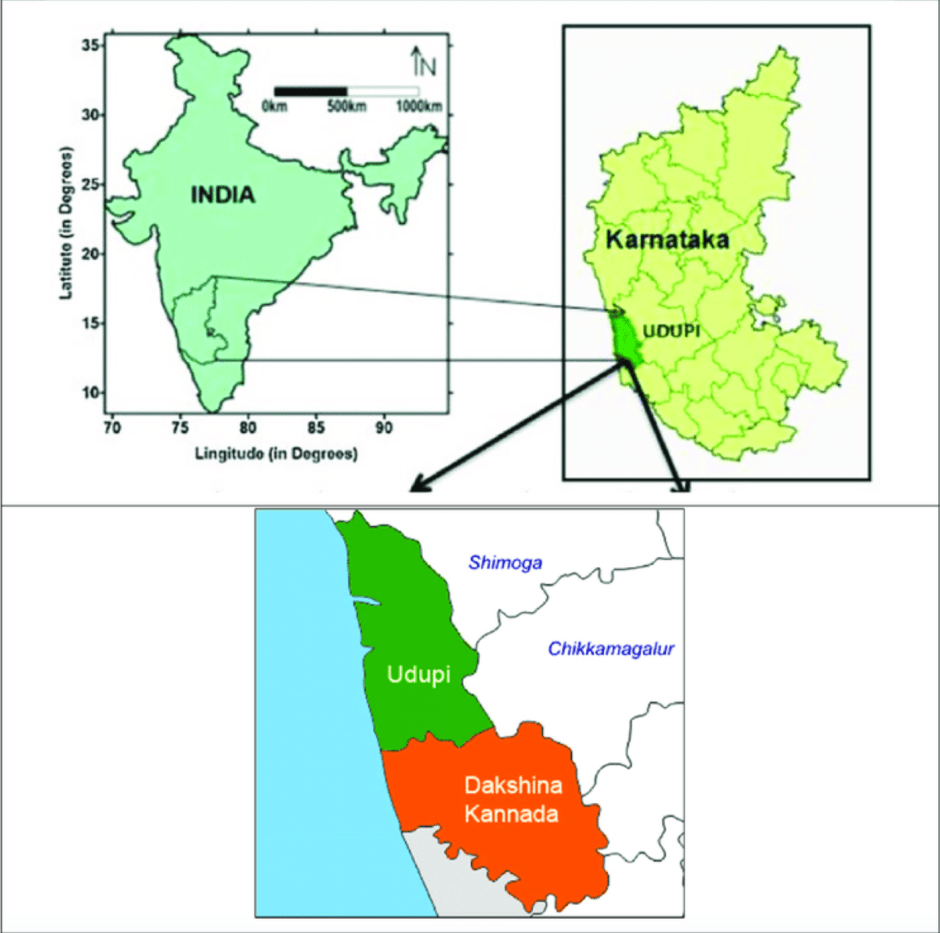

In this paper, we will be discussing the phenomenon of the Mangalore Stores taking place in the urban landscape of Bengaluru (erstwhile Bangalore) in the state of Karnataka, India. Amidst big supermarkets like Reliance and Spar, Mangalore Stores are hyper-local shops that sell food items from the Mangalore region (which encompasses the Dakshin Kannada region, that is, the Southern, coastal region) located in South Karnataka (see map below). These include both fresh produce and homemade snacks that are specific to this region. According to informal estimates, there are about 300–400 Mangalore Stores in Bengaluru alone. These small shops are neither officially affiliated with each other, nor do they all fall under a common corporation of Mangalore Stores. But they share ‘Mangalore Stores’ as a common name (sometimes altering it to ‘New Mangalore Stores’) and sell similar products.

These shops are scattered across Bengaluru, in various localities. We were intrigued by these spaces, not just because of the specificity and origin of their products but also because of the atmosphere that was created in the stores. The Mangalore Stores in these locales are akin to cultural hubs, spaces that encourage a shedding of the unidimensional roles of owner or customer and draw people into relations with each other based on their common association with their place of origin—the Mangalore region. We conducted interviews with the shop owners and their customers at three Mangalore Stores in different locations and neighbourhoods across Bengaluru. Our interviews yielded stories of migration, gastro-nostalgia, and a retrieval of identity. In this paper, we examine how emotions—particularly gastro-nostalgia, through the consumption of the food of one’s own group—are evoked by Mangalore Stores and its products, among migrant customers who are trying to make sense of their new surroundings through the store.

Literature Review

Migration and Loss—Food and Memory

Bengaluru is considered one of the major IT hubs of India and has gone from a sleepy retirement town in the colonial era to ‘India’s silicon valley’ in the neoliberal era.1 Literature about Bengaluru is dominated by this narrative of a growing urban sprawl that is becoming competitive as a global city.2 While these studies look at Bengaluru from the context of a global city and thus try to analyse the foodways of Bengaluru through this lens, they neglect the fact that Bengaluru itself is not a homogenous entity. While cuisine and restaurants have begun to see a globalising influence through the advent of many international chain restaurants, Bengaluru’s local foodways has also undergone a shift in the opposite direction; emphasising the domestic. Mangalore Stores caters to a regional, hyperlocal population. There is a dearth of literature available on Mangalore Stores, its origins, history, and workings.

Urban spatiality is reconfigured by migrant populations through practices of everyday life by renegotiating ideas of home and belonging. As an ever-expanding city, Bengaluru’s population is also constantly in flux. A 2019 Times of India article predicted that Bengaluru’s migrant population would exceed 50% by 2021. As Bengaluru went through waves of development and modernisation, studies also looked at the reasons for migration—whether people are being ‘pushed’ out of rural areas or ‘pulled’ towards urban areas.3 Such dislocation and movement carry with them cultural narratives of identity, memory, and place-making. According to James Farrer4, migrants to urban spaces may downplay their national identity in favour of a regional identity. The regional identity of Mangalore Stores and their accompanying food practices come with their own cultural narratives of identity, memory, and place-making. In fact, Karrholm et al. argue that translocal communities change the scale of space itself.5

The first Mangalore Stores was opened in 1995 in Malleshwaram. The owner told us that they “started the store to provide uru-side snacks.”6 It was important for the owners, themselves having migrated recently, to have the food products of their home more easily available in Bengaluru. It has been thirty years since the opening of this store, and Mangalore Stores have since ballooned across the city, with stores in almost every neighbourhood. These stores, all named Mangalore Stores, even though they may not always be affiliated with each other, have a specific brand—they all sell the same food products. This includes packaged snacks like Chakkali and Kodbale7 and freshly prepared food items like Patrode8 and Kotte Idli9. The layout is also usually similar, with packaged food stocked in the shelves along the walls, the prepared snacks on the counters near the billing area, and the fresh vegetables displayed outside the store. This familiar arrangement of the stores coupled with other markers of ‘Mangalore-ness’—like the Ideal brand’s ice cream specific to, and famous in, the Mangalore region—bring about gastro-nostalgia in the customers through the familiarity of the products and their taste, as well as of the layout of the store.

Identity and Migration

Claude Fischler shows that “you are what you eat” by illustrating the significance of food in identity construction, not just individual but also communal.10 A person’s choice of food links them to the larger community they are a part of or excludes them from it. Food—what can be eaten, when, and how—can define a person’s place in the hierarchy of their community. As such, choosing what to eat is not an innocuous decision. It implicates a person’s relationship with the different parts of their identity—be it a strengthening of their roots or a transgression from it. However, identity is also not a stable entity, especially in a rapidly globalising world with an accelerated process of cultural exchange, or ‘flow’ as Arjun Appadurai calls it in Modernity at Large.11 He cites the rise in migration as one of the ‘flows’ contributing to the changing global cultural dynamic. Occurring alongside the flows of capital, media, images, and ideas, they create “uncertain landscapes.”12 Appadurai argues that in such a scenario, there are few fixed points or certainties against which individual and group identity can be formulated.13 In the face of such uncertainty, individuals feel more strongly that they need to assert their identity—to hold onto and reinforce the links to one’s own culture, whatever shape that may take. Mangalore Stores becomes a site for such identity markers. With its explicit reference to the region, and its deliberate attempts to root itself in that food culture, Mangalore Stores become a place where migrant customers can reconcile their changing identities.

For migrants, food becomes a significant aspect of navigating a shifting identity. Through different ways of interacting with the host place—acculturation, adaptation, or resistance—migrants make sense of their belonging both to their hometown and their host place. According to Fabio Parasecoli, “immigrants cope with the dislocation and disorientation they experience in new and unknown spaces by recreating a sense of place around food production, preparation, and consumption, both at the personal and interpersonal levels.”14 While migration is a kind of displacement, where migrants’ sense of place and belonging shifts in their day-to-day life, food becomes a way of ‘anchoring’ the migrants’ identity, “stem[ming] loss and promot[ing] continuities in a migrating context.”15 Mangalore Stores create a home away from home by allowing people to hold on to their food practices.

Place-making Practices

An important aspect in migration narratives is how people make sense of the surroundings they have migrated to. According to Yu Fi Tuan, experience plays a significant role in shaping space and place.16 While space is more abstract, place is concrete and defined, given meaning by people’s experiences and how they relate to it.17 Place is where home and belonging is located.18 As such, place-making becomes an important way for migrants to make sense of their surroundings, making a home in it. It is a way of forging a community identity and also of articulating the aspiration of this community.19 Arijit Sen explores the everyday interactions with food informed by immigrant identities and place-making through Bangladeshi fish stores in Chicago.20 Everyday engagements with particular food products can reveal cultural memories and reproduce specific forms of food practices, as we found in Mangalore Stores too. Place-making and migration are twofold; they involve the processes of looking back and remembering as well as adapting to the present environments.21

Through our paper, we want to argue that Mangalore Stores invoke powerful discourses of home, family, and community—through the consumption of the food of one’s own group. The space of Mangalore Stores itself is significant to the construction of a home away from home. As Purnima Mankekar has argued in her study of India stores in the USA, the stores enable a construction of India and Indian culture.22 Similarly, Mangalore Stores constructs such a space through its layout, and through the shopkeepers’ conscious use of native languages. As such, nostalgia is used as branding in the form of food products sold in Mangalore Stores, and the ‘familiar’ is retailed. The food products sold in Mangalore Stores create “regimes of value” as they move from South Karnataka to urban Bengaluru.23 By regimes of value, Mankekar means that consumption always takes place within certain social and cultural contexts. As such, the meanings of the commodity and its consumption are contingent on such context rather than being absolute. We can see that food items sold in Mangalore Stores may take new meanings compared to their consumption and preparation at home.

Place-making is a way of forging connections between people and the places in which they live.24 Here, sensorial experiences become crucial. Embodied experiences of touch, taste, smell, all play a role in forging these connections through memory. As such, food becomes one of the primary ways of place-making. Cook and Crang (1996) look at food as material culture and how food and culinary practices are always geographically displaced.25 By this, they mean that it is important to consider not only the rooted and local but also the movements from one place to another. Such a conception brings into question the idea of ‘original’ and ‘authentic’. Thus, the geographical knowledge of food and food practices includes both the local place of food consumption and also the larger network of foodways involved in producing the food. Food becomes an important aspect of place-making, both through sensorial experience and through geographical knowledge. Consequently, Bengaluru’s urban foodways, and the role played by Mangalore Stores, become significant when it comes to the customers’ migrant identity and belonging.

Objectives and Methods

At the beginning of our study, our research focus had been on Mangalore Stores and its products as an example of a regional store in Bengaluru. We conducted a pilot study of a Mangalore Store in the Hulimavu area of Bengaluru. For this, we spent time in the shop, observing the interaction between the customers and store owners. We also conducted a semi-structured interview with the store owner. With this data in hand we were able to formulate more pointed research questions about Mangalore Stores as a space and the role that it played in the Mangalore migrant’s experience of Bengaluru. We expanded the study to three different stores spread across Bengaluru. The Hulimavu store was relatively new, less than a year old, and was the smallest of the three stores. The JP Nagar store, then three years old, opened with the support of another Mangalore Stores nearby. It had a unique feature—a live kitchen counter. The Malleshwaram store is the oldest Mangalore Store in Bengaluru, opened in 1995. We were told by the shopkeepers that most of them had initially worked in the Malleshwaram store before consequently opening their own stores across different locations in Bengaluru. A majority of the products are also sourced through the Malleshwaram store.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with the shopkeepers of the different stores. We also conducted short interviews with customers. These were conducted as we engaged with the customers in the middle of their errands—we interviewed them just outside the store as they finished their shopping. We also spent time in the stores observing the interactions between the customers and shopkeepers, and how customers navigated the store. This allowed us to see the kind of familiarity the customers had with the shopkeepers and the layout of the store.

Theoretical Framework: Gastro-nostalgia

Tulasi Srinivas, in her study of Bengaluru’s urban foodways, proposes the frameworks of gastro-nostalgia and gastro-adventure to capture and examine the gustatory activities of a “postmodern urban identity”.26 While gastro-adventure involves the consumption of unfamiliar or new food, gastro-nostalgia is linked to the consumption of food of one’s own culture or group. This, Srinivas argues, is a way of knowing oneself and one’s history (88). Gastro-nostalgia is thus a link to one’s individual identity and also something that reinforces the individual’s connection to their community and culture. The anxiety over one’s identity is often reconciled through the symbolic consumption of food. Srinivas argues that for Bangalorean cosmopolitans, the recovering of one’s identity through ‘authentic’ food of one’s caste, ethnicity, and locale is seen as a “good enterprise leading to knowledge and awareness”.27 Here, Srinivas specifically uses the word ‘authentic’ to point to how narratives of identity and belonging are linked to food consumption.28

In our study of Mangalore Stores, we found that many of the customers who came to the store were there for a ‘gastro-nostalgic’ experience. Through the consumption of Mangalore Store products, customers sought a “retrieval of the self”.29 In an article titled, “A’s Mother Made It’: The Cosmopolitan Indian Family, ‘Authentic’ Food, and the Construction of Cultural Utopia”, Srinivas has examined how the quest for gastro-nostalgia has been fuelled by “meta-narratives of loss”.30 There are several narratives within this; of striving for ‘authenticity’ and of a nostalgia for food ‘as mother made it’. She argues that there is a twofold movement happening because while people want to keep their traditions alive and pass them on to their children, they are also required to participate in a globalised world in which speed is key. Mangalore Stores lies at this intersection as it associates itself with tradition and authenticity while at the same time delivering convenience in the form of prepared and packaged foods. We have used the framework of gastro-nostalgia in order to examine the customers’ experiences of Mangalore Stores and the role its food products play in addressing a shifting sense of place and identity.

Findings and Discussion: Uru in Bengaluru

R.E. Pahl critiques Louis Wirth’s notion of urban life and the urban personality as predominantly impersonal, anonymous, and interchangeable.31 Pahl cites studies conducted across various major cities like London, Cairo, and Delhi that found that city centres see a lot more close relations than is assumed by Wirth. He calls these “urban villages,” and they are formed through “high level[s] of social cohesion based on interwoven kinship networks and a high level of primary contact with ‘familiar’ faces”.32 The existence of such urban villages shows that a city is not homogeneous and that urban institutions do not exert a uniform force on every space or community. Urban spaces enjoy a diversity of cultures and relationships, and it is the existence of such differences that allows for regional stores like Mangalore Stores to find their place in a city like Bengaluru.

During our interviews, we encountered the idea of the uru, as used by both owners and customers to refer to where the food products were sourced from. Uru in Kannada, a language spoken in the state of Karnataka, translates to village. But the word also carries with it connotations of nativity—a ‘hometown’. It is in the uru that dishes like Patrode, Kotte Idli, and Korri Rotti33 were made, and that the people of Bengaluru come in search of, at these Mangalore Stores. The shop owners emphasise this connection to the uru; it is where their homeland is, from where they source their products, and from where the majority of their customers come. The process of migrating to, and subsequent settling in Bengaluru, led to a loss of ingredients and foods from the uru that are being retrieved through these stores. Perhaps there is less time to cook now, or maybe the ‘authentic’ ingredients are just not available in the supermarkets—these Mangalore Stores stock it all. Run by people from the uru, for the people of the uru, these stores are an oasis of familiarity in which the owner and the customer both rejoice. Whether it be the kinship of Kannada, Tulu, and Konkani (languages spoken in the Mangalore region), or the love of South Karnataka snacks like Chakkali and Kodbale and vegetables and greens like the Mangalore Cucumber, Thonde Kai (Coccinia grandis or Ivy Gourd), Ondelga (Centellia asiastica), and Basale (Basella alba), Mangalore Stores provide it all.

Our interviews with the customers of Mangalore Stores were threaded with narratives of loss. Migration from the rural and semi-rural areas of Mangalore to the urban locales of Bengaluru implies not only a change in the availability of ingredients but also a drastic one in lifestyle and family systems. While it is evident that not all vegetables are easily available in the Bengaluru markets to cook one’s home food, it is also true that a lack of time and support systems means that people can no longer afford to prepare and stock the snacks they had grown up eating. First generation migrants may remember these vegetables and dishes, but a second generation migrant is further removed. Not only is there a loss of specific dishes in the household but also of the knowledge of different ingredients and flavours and of the ways of preparing. Mangalore Stores act as a link between the migrants and their life in the uru, stocking vegetables and fruits as well as ready-to-eat snacks. A prime example of this is the Ellu Bella, a sweet dish consisting of sesame seeds, jaggery, groundnuts, sugar crystals, and dry coconut—prepared for the festival of Sankranti.34 This dish is time-consuming to prepare, as it requires a lot of chopping of dry coconut and jaggery. It is also cumbersome because the coconut needs to be dried in the sun before chopping. During the festival, Mangalore Stores stock up on Ellu Bella, allowing people to celebrate the festival in a different setting, while also ensuring a certain stamp of ‘authenticity’ as the dish is guaranteed to be coming from the uru, or to be prepared by someone from the uru.

Migration does not only imply the material loss of place and access to ingredients. It also implies an anxiety over a shifting identity, and as mentioned above, food becomes an integral way of ‘anchoring’ this identity.35 Mangalore Stores guarantee that the products they sell are from the region and are thus ‘authentic’. Their supplies come from the Mangalore region in overnight buses and the shops have contacts in the locality—people who are from the uru—who can freshly prepare the packaged snacks every day. Migrants from the Mangalore region in Bengaluru choose to frequent Mangalore Stores because it is a way of ‘retrieving the self’, as Tulasi Srinivas terms it.36 The anxiety over one’s identity is often reconciled through the symbolic consumption of food. Even if certain products are available in the supermarket, people prefer to buy them from Mangalore Stores because it ensures that the products are the ‘real deal’.37 A customer told us that they come to Mangalore Stores specifically to “eat [their] native food”. Mangalore Stores operate on this notion of authenticity.

Fischler points out that in a modern and industrialised world the relationship between food and identity has become ‘problematic’.38 This is because of the advent of prepared and packaged foods that are cooked before they enter the household, in a process that obscures the origin and process of production of a food item from the people eating them, people who are merely ‘consumers’ in this equation. Moreover, the food itself is constituted differently in its packaged form, “tending to mask, imitate and transform ‘natural’ and ‘traditional’ products [so that] we know less and less what we are really eating”.39 Devoid of its history and cultural specificity, the modern industrialised world can often create a food with no identity.

In such a scenario, Mangalore Stores avidly try to link food and identity by marketing its products as ‘authentic’ and ‘traditional’ Mangalorean items that allow consumers to feel more connected to their Mangalorean identity even as they purchase the ready products rather than preparing them at home. Mintz and Du Bois point out that much like a nation, a cuisine is also imagined.40 Mangalore Stores reinforces the connection between a Mangalorean identity and its attendant cuisine through the products sold in the stores. A prime example is the brinjal variety specific to the Mangalore region (Udupi, specifically) called the Mattu Gulla. This variety of brinjal also has a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. It is grown in the Mattu village and Mangalore Stores stock this vegetable for sale as its GI tag makes it undeniably Mangalorean, and proudly so. Food is more than its component parts. It is “a complex set of relations, social and environmental”.41 Mangalore Stores claims that all of its products come from in and around the Mangalore region itself, thus drawing a direct link to the uru. The ready snacks are also freshly prepared everyday by local migrants themselves. This also demystifies the products and allows customers to feel as though the products are coming to them from households in the uru and not an impersonal shop. In this way, Mangalore Stores try to construct a stamp of authenticity; one that is echoed by the customers through their gastro-nostalgia, and a retrieval of their cultural identities through the consumption of these foods.

A customer from the Malleshwaram store claimed that Mangalore Stores is where they come to “buy products from [their] culture”, while another customer from the Hulimavu store said that this is “like [their] own store”. The customers and shopkeepers alike see Mangalore Stores as a way of connecting with their home and their culture. It keeps the traditions of home alive, not only through the food products being sold, but also by creating a space in which Mangalore is recreated. Shopkeepers talked about the importance of knowing the different languages spoken in and around Mangalore (Kannada, Tulu, Konkani) in order to connect with the customers and assure them that they are home. Customers value Mangalore Stores because it is a link to their culture, something they will not get in other stores.

The stores do not advertise much, nor do they need to. They rely on the networks of connections and word of mouth by migrants living in the locality. The name of the store itself acts as an advertisement and draws customers because it indicates a certain subcultural affiliation that draws customers who may be familiar with it or belong to it. The JP Nagar store owner told us that the store was opened in this location because of the predominantly native Mangalorean population of the area. He went on to say that “they give our contact to others, locals, who then also come to us. It goes customer to customer. So we ourselves don’t advertise much”. He also pointed out that ‘real’ Mangalore Stores necessarily sell Mangalore vegetables and Ideal’s ice cream. Such markers of familiarity become advertisement enough. The people who are ‘in the know,’ so to speak, recognise the food products not simply as food, but as their own food; the sight of which is enough to draw customers who may be walking by. They may recognise the Mangalorean cucumber stocked in the venerable rack or the poster for the Ideal ice cream brand.

The sensorial experience of Mangalore Stores as a space becomes a crucial way of place-making. Here, the embodied experience of the prepared food products, packaged foods, and vegetables—the touch, taste, smell—all play a role in forging connections to a nostalgic ‘home’ through memory. The layout of the JP Nagar store is such that the prepared snacks are heated up in the store itself in the evenings. The smell of butter and roasting Patrode wafting through the store evokes strong feelings of home and belonging. The Hulimavu store has a small outdoor area where we interviewed a family of four as they feasted on their Ideal’s ice cream. The shopkeepers all also make it a point to know the different languages spoken in the Mangalore region and connect with the customers personally. The Malleshwaram store owner told us, “That is how we have survived here for so many years. By familiarising ourselves with the people who come regularly, knowing what products they usually buy.” Mangalore Stores recreate the Mangalore region within their space, as customers and shop owners interact in their own language and reproduce the customs and ways of address of the region, along with the sensorial experiences of the tastes, smells, and feel of home food.

Conclusion

Mangalore Stores are hyperlocal stores in Bengaluru, selling regional food products and gastro-nostalgia to customers. The store creates a space for migrants to feel at home in a new setting. The loss of ingredients and foods from the uru are retrieved through these stores—bringing the uru closer to the customers in Bengaluru. Customers are able to soothe their anxiety about their changing identity by stepping into the store and reinforcing their Mangalorean identity. Here, it is not just the consumption of the food products that facilitates this regaining of identity but also sensorial experiences of the space of the stores. But Mangalore Stores are also a part of the heterogeneous urban space of Bengaluru and thus cater to a blend of people and not just migrants from the Mangalore region. Mangalore Stores also create a space that becomes an avenue for ‘gastro-adventure’, where people unfamiliar with the food from the Mangalore region can experience and experiment with its food items. This dynamicity of Mangalore Stores is scope for further research.

- Nair, The Promise of the Metropolis, 19. ↩︎

- Pani, Resource Cities Across Phases of Globalization; Narayana, Globalization and Urban Growth; Ramachandra et al., Modelling Urban Revolution. ↩︎

- Sridhar et al., Is It Push or Pull. ↩︎

- Farrer, Urban Foodways: A Research Agenda, 98. ↩︎

- Karrholm et al., Migration, Place-Making and the Rescaling of Urban Space. ↩︎

- ‘Uru’ means ‘village’ in Kannada, one of the languages spoken in the Mangalore region. It is used in the sense of ‘home-town’ in this context. Here, uru-side snacks refers to the snacks originating from the shopkeepers’ and customers’ native places or hometowns in the Mangalore region. ↩︎

- Chakkali and Kodbale are fried savoury snacks. ↩︎

- A local Mangalorean delicacy prepared with Kesuvu (Colocasia Esculenta) leaf. ↩︎

- A steamed dish prepared with black gram lentils. This dish is special because it is steamed inside a cup made of jackfruit leaf. ↩︎

- Fischler, Food, Self, and Identity, 280. ↩︎

- Appadurai, Modernity at Large, 33. ↩︎

- Appadurai, Modernity at Large, 43. ↩︎

- Appadurai, Modernity at Large, 44. ↩︎

- Parasecoli, Food, Identity, and Cultural Reproduction in Immigrant Communities, 416 ↩︎

- Abbotts, Approaches to Food and Migration, 117 ↩︎

- Tuan, Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective, 388. ↩︎

- Tuan differentiates between space and place, and states that space is something that is abstract and cannot be ‘apprehended’ through human perception and conception (388). Place, on the other hand, is experiential. Place is a concrete location in space. More than location, it is an ‘ensemble’ that includes cultural, philosophical, and historical nodes (Tuan 399). As such, place-making is a practice that connects a community member to their space (Ellery et al.). In this paper, we use the idea of place to examine the role of Mangalore Stores in forging such connections. ↩︎

- Bamba and Haight, as qtd. in Ellery et al., Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. ↩︎

- Pemberton and Phillimore, Migrant Place-Making, 2. ↩︎

- Sen, Food, Place, and Memory. ↩︎

- Sen, Food, Place, and Memory, 68, 79. ↩︎

- Mankekar, India Shopping, 75-98. ↩︎

- Mankekar, India Shopping, 82. ↩︎

- Ellery et al., Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. ↩︎

- Cook and Crang, The World on a Plate, 132. ↩︎

- Srinivas, Everyday Exotic, 87. ↩︎

- Srinivas, Everyday Exotic, 100. ↩︎

- Srinivas, Everyday Exotic, 88. ↩︎

- Srinivas, Everyday Exotic, 100. ↩︎

- Srinivas, As Mother Made It, 356. ↩︎

- Pahl, The Rural Urban Continuum. ↩︎

- Pahl, The Rural Urban Continuum, 302. ↩︎

- A crunchy, crispy wafer prepared with ground rice. It is popularly consumed with chicken curry, hence the name Korri Rotti (Korri meaning chicken). ↩︎

- Sankranti is a harvest festival celebrated in Karnataka. It falls in the month of January and people celebrate by distributing Ellu Bella and fruits like sugar cane and banana to the houses in the neighbourhood. ↩︎

- Abbots, Approaches to Food and Migration, 117. ↩︎

- Srinivas, Everyday Exotic, 100. ↩︎

- The ingredients for the food items come from the uru and are prepared by migrants from the uru. ↩︎

- Fischler, Food, Self, and Identity, 289. ↩︎

- Fischler, Food, Self, and Identity, 289. ↩︎

- Mintz and Du Bois, The Anthropology of Food and Eating, 109. ↩︎

- Stiles et al., The Ghosts of Taste, 225. ↩︎

Bibliography

“Bengaluru’s Migrants Cross 50% of the City’s Population.” The Times of India, August 4, 2019. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/bengalurus-migrants-cross-50-of-the-citys-population/articleshow/70518536.cms.

Abbots, Emma-Jayne. “Approaches to Food and Migration: Rootedness, Being, and Belonging.” In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology, edited by Jakob Klein and James L. Watson, 115–132. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Cook, Ian, and Philip Crang. “The World on a Plate: Culinary Culture, Displacement and Geographical Knowledge.” Journal of Material Culture 1, no. 2 (1996): 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/135918359600100201.

Ellery, P. J., H. R. Ellery, A. R. Borkowsky, and C. L. Corkery. “Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking.” International Journal of Community Well-Being 4 (2020): 55–76. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42413-020-00078-3.

Fischler, Claude. “Food, Self, and Identity.” Social Science Information 27, no. 2 (1988): 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901888027002005.

Kärrholm, Mattias, Sara Westin, and Maria Stigendal. “Migration, Place-Making and the Rescaling of Urban Space.” European Planning Studies 31, no. 2 (2022): 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2038544.

Mankekar, Purnima. “’India Shopping’: Indian Grocery Stores and Transnational Configurations of Belonging.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 67, no. 1 (2010): 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840220122968.

Mintz, Sidney W., and Christina M. Du Bois. “The Anthropology of Food and Eating.” Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (2002): 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.032702.131011.

Nair, Janaki. The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Narayana, M. R. Globalization and Urban Growth: Evidence for Bangalore (India). University of Tokyo: CORE, 2008. https://core.ac.uk/works/6581234.

Pahl, R. E. “The Rural Urban Continuum.” Sociologia Ruralis 6, no. 3 (1966): 299–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1966.tb00537.x.

Pani, Narendar. “Resource Cities Across Phases of Globalization: Evidence from Bangalore.” Habitat International 33, no. 1 (2009): 114–119. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197397508000428.

Parasecoli, Fabio. “Food, Identity, and Cultural Reproduction in Immigrant Communities.” Social Research 81, no. 2 (2014): 415–439. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26549625.

Pemberton, Simon, and Jenny Phillimore. “Migrant Place-Making in Superdiverse Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 55, no. 4 (2018): 733–750. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26958503.

Ramachandra, T. V., Bharath H. Aithal, and G. Sen. “Modelling Urban Revolution in Greater Bangalore, India.” Paper presented at the 30th Annual In-House Symposium on Space Science and Technology, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, 2013. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258316417.

Sen, Arijit. “Food, Place, and Memory: Bangladeshi Fish Stores on Devon Avenue, Chicago.” Food and Foodways 24, no. 1–2 (2016): 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2016.1145026.

Sridhar, Kala Seetharam, Arjun Kumar, and V. S. Anil Kumar. “Is It Push or Pull? Recent Evidence from Migration into Bangalore, India.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 14 (2013): 287–306. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12134-012-0241-9.

Srinivas, Tulasi. “‘As Mother Made It’: The Cosmopolitan Indian Family, ‘Authentic’ Food, and the Construction of Cultural Utopia.” In Food and Culture: A Reader, 3rd ed., edited by Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik, 355–370. New York: Routledge, 2013.

———. “Everyday Exotic: Transnational Space, Identity and Contemporary Foodways in Bangalore City.” Food, Culture & Society 10, no. 1 (2007): 85–107. https://doi.org/10.2752/155280107780154141.

Stiles, Kaelyn, Ozlem Altiok, and Michael M. Bell. “The Ghosts of Taste: Food and the Cultural Politics of Authenticity.” Agriculture and Human Values 28 (2011): 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-010-9265-y.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. “Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective.” In Philosophy in Geography, edited by Stephen Gale and Gunnar Olsson, 387–427. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. Originally published in 1979.

Biography

Shreya R is an editorial assistant at the Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS) Journal. Her research interests include narratives, narratology, and urban studies. In her free time, Shreya likes to read to occupy her mind and crochet to occupy her hands.

Mahika Mor is a travel enthusiast, a yoga facilitator, and a plant mom. Mahika’s research interests include popular culture and literature, modern mythology, and critical food studies. She is often found lost in a fantasy novel and dreaming of faraway lands.